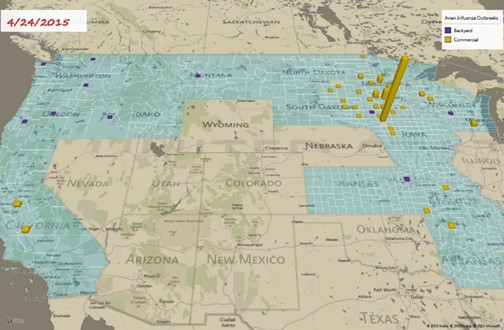

At present, the recent outbreak of the bird flu has been found on 58 farms across 13 states in the U.S. The majority of those are located on 31 farms in the top turkey state of Minnesota. The United States Department of Agriculture estimates total birds on those 58 farms which have been/will be culled at 6.928 million head. Only two egg operations have been hit so far, the one in Osceola County, Iowa and one in Wisconsin. All the other cases in the Midwest have been at commercial turkey farms.

What is the bird flu? There are two strains of bird flu viruses that have been identified in the Pacific Flyway (or migratory bird paths): the H5N2 virus and new H5N1 virus. The new H5N1 virus is not the same virus as the H5N1 virus found in Asia that has caused some human illness.

Since 2003, a growing number of countries, starting in south east Asia, have reported outbreaks of bird flu in chickens, turkey, and ducks. The virus can spread rapidly through flocks of domestic poultry. In the past, more than fifty countries have had H5N1 outbreaks among birds, leading to 200 million birds that have died or been culled.

So what does economics say about bird flu infection? This all comes down to biosecurity. Note that infectious disease prevention is a public good according to principles of economics. So, biosecurity broadly falls in to the subject of public economics, but is deeply rooted in the principle of micro-economics.

One of the key behaviors affecting the spread of infectious disease is the degree to which individuals self-protect from disease risks, either through immunization or other fundamental biosecurity effort. Strategic behavioral interactions can arise when poultry farmers make self-protection choices. An individual farm's disease risk can depend on the self-protection behavior of other farms. Individual self-protection behavior is an example of an economic behavior that generates positive externalities/spillovers affecting the supply of a public good, i.e., infectious disease prevention.

In this instance, there are two types of strategic interactions. The first one is a strategic complement. One individual's marginal incentives toward self-protection can increase with the self-protection of others. This will enhance the potential for coordination among poultry farms. The second one can be a strategic substitute. An individual's marginal incentives for self-protection decline with the self-protection of others. In this case, poultry farms assume that they don't necessary need to be so vigilant because others are self-protecting.

Some recent studies find that self-protection to reduce spread of an existing livestock disease between herds is a strategic substitute, while others conclude that self-protection to prevent the introduction of a new livestock disease into a region is a strategic complement. We can explicitly investigate these strategic interactions among poultry farms by applying simple game theory framework in economics.

To see a quick video showing the progression of cases over time, click here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-mWOmZ09JMU&feature=youtu.be.