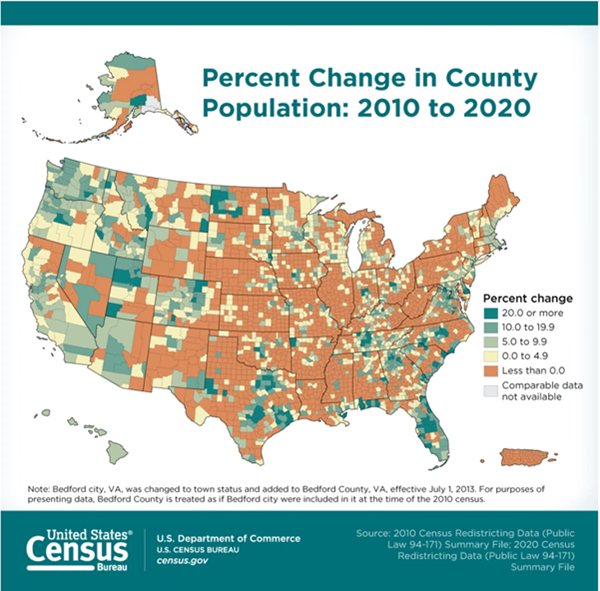

The U.S. Census has released the data from the 2020 census. As the map below shows, a significant number of rural areas between the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachian Mountains lost population during the past decade. Much of this population loss occurred even though many of those counties are in states that had net population gains – meaning the population concentrations in metropolitan areas continue to increase. In fact, only three states experienced population declines: Illinois, Mississippi, and West Virginia. But even within these states, there were metropolitan areas that had population gains. Across the U.S., the net population gain was 7.7%[1]; however, completely rural areas saw a 2% decline in population.

Some of the notable exceptions to rural population losses were in the areas with energy expansion (western North Dakota, parts of Texas and Oklahoma, and areas in Ohio), as well as areas that have emerged as new retirement and recreation areas such as Kentucky, Tennessee, and northern areas of Alabama and Georgia. Additionally, many rural areas west of the Rocky Mountains gained population.

What does this mean for agriculture? First, it means that employment in rural areas will continue to lag behind employment growth in metropolitan areas. Suburban areas are where more rapid employment opportunities continue to expand. This means that more of the food and agricultural supply chain that is beyond the farm is likely to shift from rural areas to suburban areas. This includes much of the processing, packaging, and marketing activities that add value to agricultural production. Between 2010 and 2018, USDA-ERS reports that completely rural, nonadjacent counties experienced a decline in overall employment (-0,4%) whereas metro areas saw a 1.5% annual increase in employment.

Farms will get bigger and continue to mechanize and adopt automation technologies. While this is just a continuation of a trend that is more than 100 years old, it is also a response to the increasing challenge of hiring and retaining labor in agricultural production. Upward pressure on wages will also encourage more displacement of labor with automation and mechanization. Rural communities where farming is a significant source of employment and local revenue flows will continue to shrink as services in those areas re-size to fit the shrinking number of farms serviced.

The farm-to-retail spread for agricultural commodities is likely to continue to expand as less and less production is consumed in rural areas. Consumption in urban areas is rapidly shifting to more ready-to-eat formats for foods consumed away from home and foods consumed at home. Packaging, processing, portion control, and other perceived value-adding activities and preparations will garner a greater share of the retail food dollar.

Financial support for local infrastructure in rural areas will increasingly be spread among a smaller number of farmers. Non-farmers are buying up farmland and renting that land back to the fewer farmers in business; therefore, even as the number of farmland owners and operation sizes grow, the number of farmers is declining. Furthermore, to the extent that property taxes are shiftable from landowners to farmers in the form of rents, the support for rural infrastructure maintenance and construction will – at the individual farm level – increase. Infrastructure support as a share of revenues will increase significantly faster for farmers than for metropolitan processors and other parts of the agricultural supply chain that is located near metropolitan areas.

The depopulation of rural areas also increases the cost of providing high-speed internet access as the option for hard-wired access becomes increasingly costly on a per-mile basis and with a declining population, hard-wiring rural areas becomes exponentially expensive on a per-user basis. Cellular technology and satellite technologies will, by default, become the avenues for access to advanced communications and internet connectivity, but the economic incentive for telecommunications companies to build out 5G and other advanced technologies in rural areas that are not on major transportation corridors is eroding.

Rural areas are also being “left behind” with regard to personal income growth. Per capita personal income was nearly $14,000 higher in metro areas than non-metro areas and completely rural areas lagged non-metro areas by several thousand dollars[2]. Over a lifetime, this disparity can add up to very significant differences in funds available for retirement and quality of life.

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Census

[2] USDA-ERS Rural America at a Glance, 2019 Edition.